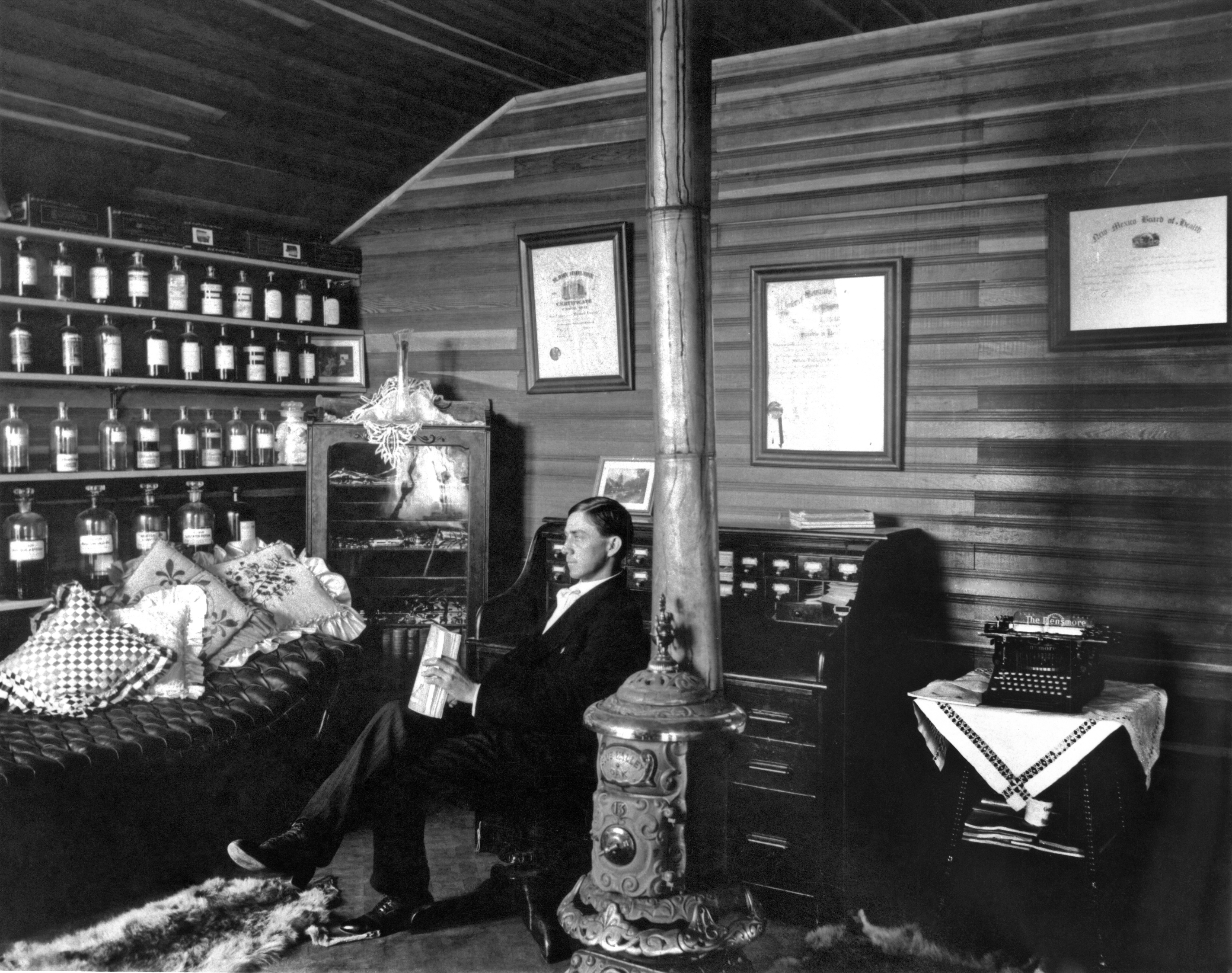

The origins of the Lovelace research laboratories and the Lovelace Hospital occurred over a century ago. In part resulting from his frustration with the limited medical capabilities of his rural practice and in part through discussions at medical meetings with Drs. Will and Charlie Mayo (who established the Mayo clinic), Dr. Lovelace formed the dream of developing a multispecialty clinical center. In 1913, Dr. Lovelace moved to Albuquerque as a means of alleviating his tuberculosis symptoms. There he established a successful private practice, became Medical Director for the New Mexico Division of the Santa Fe Railroad, and became actively involved with St. Joseph’s Hospital. The evolution of the Lovelace Clinic began as a partnership with Dr. Edgar Lassiter, who also sought respite from tuberculosis in New Mexico and who married Dr. Lovelace’s sister. The health of both physicians improved, and they had long, productive careers. The group practice expanded to become the Southwest’s first center of specialty medicine. The financially astute Dr. Lovelace acquired several properties that today comprise large sections of Albuquerque’s east side, including the Hoffmantown and Princess Jeanne developments and the land between Gibson Blvd. and Ridgecrest Dr., the site of today’s Lovelace headquarters.

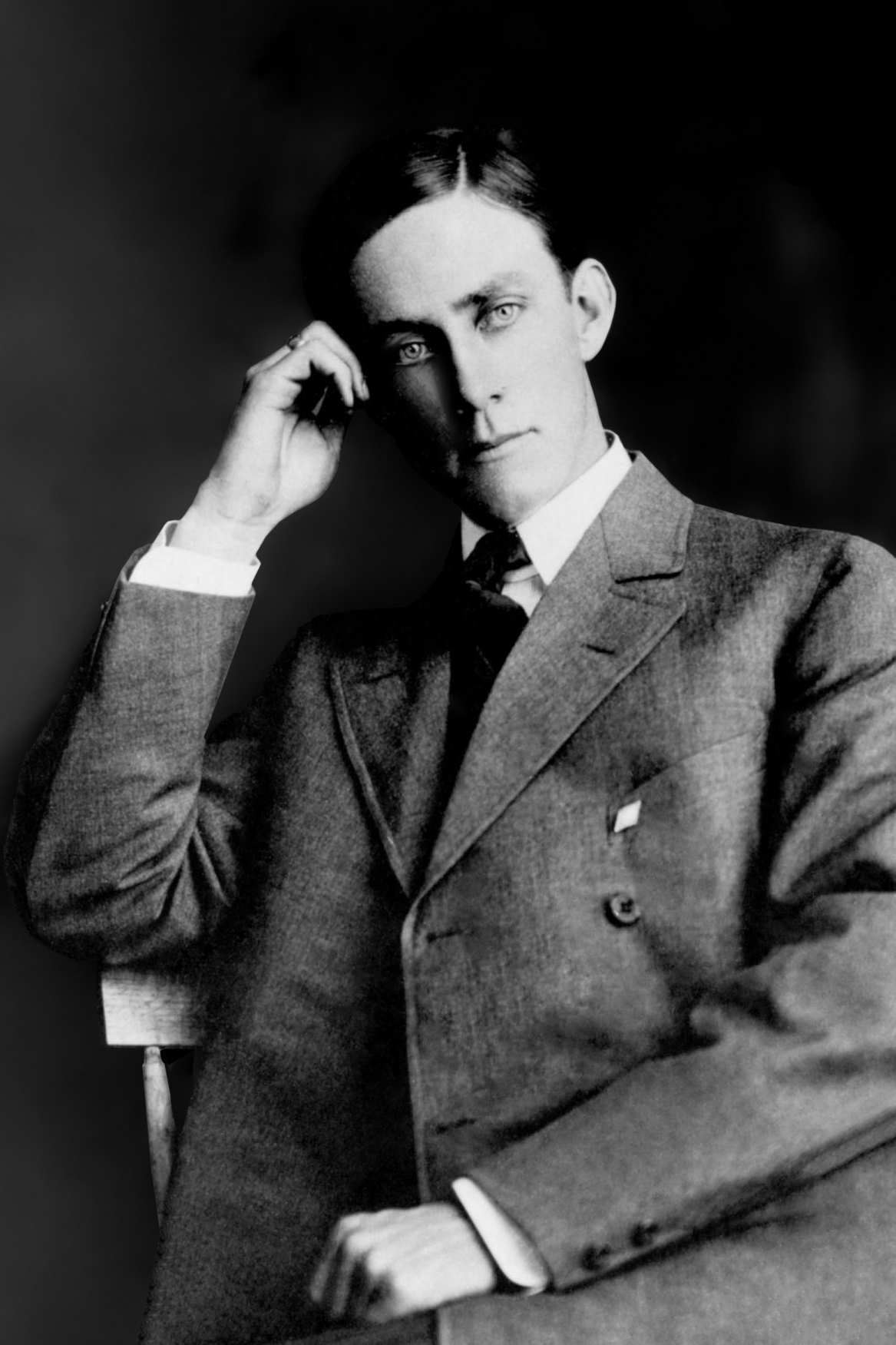

William Randolph Lovelace II (Randy) grew up on his father’s ranches, but lived with his uncle in Albuquerque while attending high school. Sharing the nation’s fascination with the rapid development of aviation during the 1920s, he joined the Naval Reserve Officer’s Training Corps and received his pilot’s license while attending Washington University in St. Louis. He pursued a medical career in the footsteps of his uncle and received his M.D. from Harvard University in 1934. His outstanding surgical skills blossomed during a fellowship at the Mayo Clinic, and he was appointed Chief of Surgery within a few years. With the impending entry of the U.S. into World War II, the Mayo Clinic was asked to form a research unit to develop solutions to the physiological challenges associated with high-altitude flight. Randy found his talent and love for research in a merger of his natural curiosity, medical knowledge, and love of aviation by joining the unit as a commissioned officer and later becoming its Chief. The unit’s several advances made Randy widely known and respected throughout the military and civilian aviation communities. A personal feat demonstrated Randy’s zest for adventure and faith in scientific principles and consolidated his recognition as a leader in aviation medicine. Lives were being lost in attempts to parachute from wounded aircraft at high altitudes without the benefit of oxygen that was available on board to the crews. Randy proposed that high altitude evacuations might be accomplished using small personal oxygen bottles, but the military brass considered the approach too radical and unlikely to succeed. Denied official permission, Randy schemed to test the method himself. Locating willing accomplices, he jumped from a bomber at 40,200 feet with a small oxygen bottle taped to his leg (incredibly, his first parachute jump!). Despite being knocked unconscious when exiting the plane, he survived the surreptitious experiment and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross when the government finally acknowledged the feat and adopted the strategy. While at Harvard, Randy married Mary Moulton (whose father also came to Albuquerque to recover from tuberculosis), and two sons and the first of three daughters were born. Polio, rather than tuberculosis, was the major health scourge in the 1940s, and tragically, despite the best medical care available, both boys succumbed in quick succession in 1946. Stricken with grief, Randy and Mary returned to New Mexico to put their lives back together. The older Dr. Lovelace encouraged Randy to join his growing specialty clinic, and in 1947 Randy agreed on the condition that the clinic would be reorganized to pursue the triple paths of health care, research, and education similar to the Mayo model (no medical school then existed south of Denver between Dallas and Los Angeles). The nonprofit Lovelace Foundation for Medical Education and Research was thus formed.

An exceptionally capable Board of Directors formed largely of outstanding business leaders and the Chairmanship of only two individuals during the Foundation’s first 40 years (Floyd Odlum and Robert O. Anderson) contributed to management stability and financial soundness. Under the astute and energetic guidance of “Uncle Doc” (as the older Dr. Lovelace was known beyond earshot) and Randy, the Foundation grew steadily in size and scope of activities through the 1950s. A new clinic facility was built at the Gibson-Ridgecrest location on the edge of town near the Veterans Administration hospital and airport, and Uncle Doc’s donation of land persuaded the Methodist Church to locate its new Bataan Memorial Hospital nearby. The medical staff and specialty care capabilities expanded, and additional research buildings were constructed. Although the Lovelace Clinic became a training ground for physicians, the organization ultimately assisted the University of New Mexico in establishing a medical school on campus.Together, the Lovelace Clinic and Bataan Hospital (which the Foundation purchased in 1969) were the sites of many medical firsts. It opened the state’s first intensive care unit, first virus laboratory, and first nuclear medicine laboratory; performed the state’s first kidney dialysis and open-heart surgery; and had the state’s first external fetal heart monitor. It also established several national and international firsts, including the first U.S. hospital having a heart-lung resuscitator, the nation’s first cystic fibrosis treatment center, the world’s first laminar flow “clean air” operating room, and the world’s first use of massive lung lavage to remove radioactive particles from a human lung. It also formed one of the nation’s earliest group health plans of the type that evolved into today’s health maintenance organizations. Faced with a challenging financial environment in the local and national health care field, a national movement toward insurance-based control of physician-patient relationships, and a need for capital investment in facilities, the Foundation sold its health care activities in the mid 1980s. Although continued use of the name “Lovelace” was granted as a condition of sale, the Lovelace Foundation became a wholly research organization at that time.Through the 1950s and 1960s, the Foundation’s research operations expanded in size, scope, and recognition in parallel with the advances of its health care activities. Randy’s interests and connections with the aviation community led to his establishing the nation’s premier center for aviation and space medicine research, and he recruited Dr. Clayton S. (Sam) White, a former naval flight surgeon, to develop and manage a broader research program. Physiological studies of commercial and military pilots led to an Air Force grant to develop a protocol for testing candidates for space flight. In 1959, under contract to the newly formed NASA, Lovelace tested 32 candidate pilots using a seven-day series of rigorous physiological and psychological tests, which culminated in selection of the seven Project Mercury astronauts. A lesser-known follow-up project demonstrated that women could pass the tests with approximately the same success rate as men, leading to the immediate inclusion of women in the Russian space program (the first U.S. woman flew into space 20 years later). Randy was appointed by President Johnson as Director of Space Medicine for NASA in 1964. Tragically, Randy, along with Mary, died in an accident when their chartered airplane crashed in the Colorado mountains in 1965. Their three daughters had not accompanied them, and the youngest, Jacqueline Lovelace Johnson, is the current Chair of the LRRI Board of Directors.

Under Sam White’s direction, the Foundation’s research expanded into additional fields, key among which were studies of therapy for blast and shock injury to the lung and the health risks of inhaled radioactive particles. These activities involved large, multi-year federal projects and required specialized facilities that could not be accommodated in the Foundation’s facilities in town. These projects were housed in government-owned facilities located on federal property adjacent to Albuquerque within what is now Kirtland Air Force Base (KAFB). Construction of the Fission Product Inhalation Laboratory began in 1962, and within two years, the program constituted one-half of the Foundation’s research funding. Under the guidance of Dr. Roger McClellan between 1965 and 1988, the facility and its staff developed into the world’s premier center for research on basic and applied inhalation toxicology. During the mid-1970s the facility was renamed the Inhalation Toxicology Research Institute (ITRI), and its scope of research expanded to encompass nonradioactive environmental and occupational air contaminants. The project developed much of the data on which estimates of health risks from lung irradiation are still based and resulted in numerous other advances in the understanding of lung biology and toxicology and health hazards from inhaled air contaminants. The Foundation created Lovelace Biomedical and Environmental Research Institute (LBERI) as a nonprofit subsidiary to operate the program. After Randy’s death and with the sale of the health care operations and associated facilities, the Foundation consolidated its non-ITRI research operations in a new building near the medical center, and research there focused on skin cancer, cell biology, immunology, imaging techniques, substance abuse, and the health sequelae of exposure to defoliant in the Viet Nam War. The Foundation also created Lovelace Scientific Resources as a for-profit subsidiary to foster new medical technologies and conduct human clinical trials of pharmaceuticals and other therapies.

By the late 1980s, the Department of Energy-funded radiation program at the ITRI facility was largely completed and being phased out, raising the possibility of the facility’s closure. ITRI encompassed a unique combination of facilities and staff that could meet other federal and nonfederal research needs, but federal ownership of the facility severely limited its access by other sponsors. Under the direction of Dr. Joe Mauderly between 1989 and 1996, the organization fought successfully to maintain its core competencies, and federal permission was sought to preserve the national research resource by allowing Lovelace to use the facility for other research obtained through competitive funding. After lengthy negotiations, the government-owned facility was privatized by granting Lovelace a long-term lease for its use for other federal and nonfederal research. This provided an opportunity, for the first time in decades, to merge the diverse Lovelace research operations into a single administrative structure. The reorganized entity was named the Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, and the new President/CEO, Dr. Robert Rubin, launched an effort to build a financially independent research enterprise focused primarily on respiratory health issues — its greatest underlying strength.

The reorganization and strengthening of Lovelace has been very successful, especially in view of the tight, highly competitive research funding environment in which it has occurred. Lovelace stands today as the nation’s largest independent, not-for-profit organization conducting basic and applied research on the causes and treatments of respiratory illness and disease. It is supported by a large, diverse portfolio of grants and contracts funded by a broad spectrum federal and nonfederal clients, and an endowment resulting from the sale of the health care operations that provides a modest level of discretionary support. A new research building was constructed in town, the research and support staff was expanded considerably, and the once underutilized ITRI facility is not only in full use as the Lovelace Inhalation Toxicology Laboratory, but has also expanded. Lovelace research includes major programs in fundamental lung biology, lung cancer detection and prevention; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, environmental inhalation hazards, and therapies for chemical, biological, and radiation exposures; and preclinical studies of new pharmaceuticals and clinical trials. Lovelace continues its historic investment in education through a pre-college science academy, undergraduate, graduate, post-doctoral, and sabbatical training programs, and the academic appointments of most of its researchers at the University of New Mexico.The Lovelace organization has withstood many stresses and undergone many changes over the years since Uncle Doc came to New Mexico. It stands proudly today as a unique, vital, and still-growing force for the improvement of human health. Based on its defining characteristics of excellence, independence, flexibility, and adaptability, it is certain to remain so for many decades to come.

Fast Facts

Founded: 1947, State of New Mexico, not-for-profit corporation

Employees: 120 PhD-level scientists, 691 technicians and support staff

Annual Budget: $92 million

Endowment: $45.5 million

Size of Facilities: 500,000 square feet

Funding Sources: Grants, contracts, philanthropy

Research Areas: Asthma, emphysema, lung cancer, inhalation toxicology, aerosol science, inhalation drug delivery, bronchitis, allergies, science service contracting, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, infectious disease, radiation studies, chemical exposure research, clinical trials, specialized software for laboratory research, and neurobiological research.